Ode to a Christmas Hymn

This Sunday I attended a Christmas party hosted by my friends Casper and Sean. In their humble Brooklyn apartment, I sang with a rather large group 62 pages of Christmas hymns. Seasonally appropriate, yes, but it was nonetheless a departure for me from my Grinchy abstention from all things Christmas.

Thanks for reading Jack’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

I used to love the Christmas season. I adored decorating in December, listening to the music, and reveling in the spirit of the season. But over the years, my attitude toward Christmas has grown increasingly bleak. This development is partly due to the deterioration of certain family relationships, but it is also largely because of the toxic positivity of the time. The truth is, I just don’t feel good enough about the world anymore to celebrate with such festive jubilee. Or at least, so I have thought.

Wearing all black from head to toe, including black eyeliner and eyeshadow, I marched with my wife Debbie and our roommate Joel over to that Christmas party and sang my heart out. And I cried. “Some of these songs just pierce through you,” Sean said when I told him about my crying, and it’s true. The one that got me was “Hark! The Herald Angels Sing.” Awash in a sea of voices, I found myself choking up during the following lines:

Mild he lays his glory by

Born that man no more may die

Born to raise the sons of earth

Born to give them second birthTruth be told, I could not sing these words. I was too busy staring at the ceiling, begging my eyes not to release the tears in their sockets, lest they ruin my makeup.

I do not really know what it is about those words that strikes me, but I will try to describe it. For the context in which they were written, the greatest hope an artist could have of creating something beautiful, was to create something that reflected the beauty of salvation in Jesus Christ. The function of art was to glorify God, to reflect divinity itself. With such high purpose, Charles Wesley endeavored to write words as astonishingly beautiful as the reality to which they pointed.

“Mild he lays his glory by,” is a reference to Philippians 2, which says Jesus did not consider divinity something to be exploited, but emptied himself to become a man (v.6). The Greek word for “emptied himself” is kenosis, which I have tattooed on my left arm. Though he was rich, Jesus became poor, for the sake of the poor. In Jesus, God chose the lowly, those who suffer under the crushing weight of greatness, as the site of divine revelation. How unlike the “Great Men” we know, for whom wealth and fame and privilege are most definitely to be exploited for selfish gain. In the incarnation, God definitively asserts the virtue of selflessness over against the pursuit of selfish gain.

And as the next verses say, it was for the glory of humanity that Christ sacrificed his glory. “Born that may no more may die / Born to raise the sons of earth / Born to give them second birth.” Setting aside the sexist language, the theology of these lines uplifts humanity. Where mortality is one of the defining features of human nature, in Christ death is overcome. Where humans are brought low by a world of sin, in Christ they are exalted to the heights of joy and peace. Where humans find themselves entrenched in the cycles and consequences of sin, in Christ they are made righteous and new. This theology is far from the “humanity diminished” of colonial Christian anthropology that I wrote about last week. In “Hark!” the exaltation of Christ entails the exaltation of human beings. In the glorification of divinity, the glory of humanity is made evident.

The hymn itself is a testament to the glory of humanity. It shows what beauty we are capable of, as the words and music are stunning. And this was not the work of just one man. While Wesley wrote most of the words in 1739, it was George Whitfield who contributed the lines “Hark! The herald angels sing / Glory to the newborn king.” Then, 100 years later, Johannes Gutenberg wrote the tune that we now know as the hymn’s melody. William H. Cummings adapted the lyrics to Gutenberg’s tune in 1855. So we see many hands went into the creation of this hymn, and over many years.

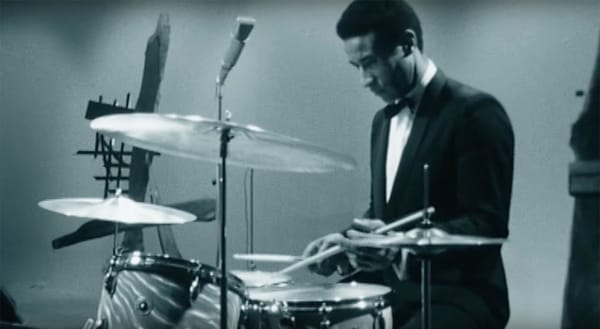

My favorite recorded version of the hymn is Nat King Cole’s. It was because of him that I first noticed the lines I quoted above, because in his version, his voice cuts out for “Hail the heaven born Prince of peace” etc., as a choir accompanying him takes those lines. Then, with grandeur, Cole returns for, “Mild he lays his glory by.” Cole’s regal, buttery voice lends the hymn a great deal of majesty.

Often when I think about hymns, I think about the many, many people throughout Christian history that have been forced to sing them. I think about imperialism, and colonialism, and Christian supremacy. I think we have so many hymns less because humans have been organically inclined to worship their savior, and more because for so many centuries Christianity has been the religion of power. Charles Wesley himself was once Secretary of Indian Affairs in Savannah, Georgia, serving the colonial project.

But despite all of this, despite disturbing contexts, sexist language, often bad theology, and questionable motivations, I join my friends Casper and Sean in admiring the beauty of Christian hymns. They transcend themselves, and they witness to the transcendent capacity in human beings for creating beauty in any situation.

Thanks for reading Jack’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.